On the Scapegoat

Examining the Christian narrative

INTRO

The [disciples] returned with joy and said, “Lord, even the demons submit to us in your name.” He replied, “I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven. I have given you authority to trample on snakes and scorpions and to overcome all the power of the enemy; nothing will harm you. (Luke 10:17-18)

From reading the works of Rene Girard, I’ve come away with a new appreciation for the Gospels, and how revolutionary the Christ narrative was for the ancient mind. He writes on how differently the ancients viewed their place in the world compared to today - that we are subject to nature and our baser instincts, with a culture and mythology that lionized the ideal of might equals right.

He indicates how the Gospels overturned this understanding. How they display the violence of the ancient world, and the victimization of the innocent inherent at the heart of it. The Christ narrative instead chooses to defend the innocent, highlighting the sanctity of the individual and the indomitability of the human spirit. Christian practice focuses on the imitation of Christ, such that we can also transcend what holds us captive.

MIMESIS

Man is the creature who does not know what to desire, and he turns to others in order to make up his mind. We desire what others desire because we imitate their desires - Rene Girard

Girard writes how most people, contrary to modern belief, lack autonomy. Rather than operate with free will, we are actually controlled by that which we desire. Neither do most know what they actually want. Our desires originate by looking to our peers, imitating what others desire. Girard terms this mimetic desire.

The religious ideal would favor imitating Christ, to renounce desire and love your fellow man. But the norm instead is to default to our false idols, to desire power, status and the approval of others. This results in violence when desire concentrates around the same objects, resulting in rivalry and conflict with our fellow man.

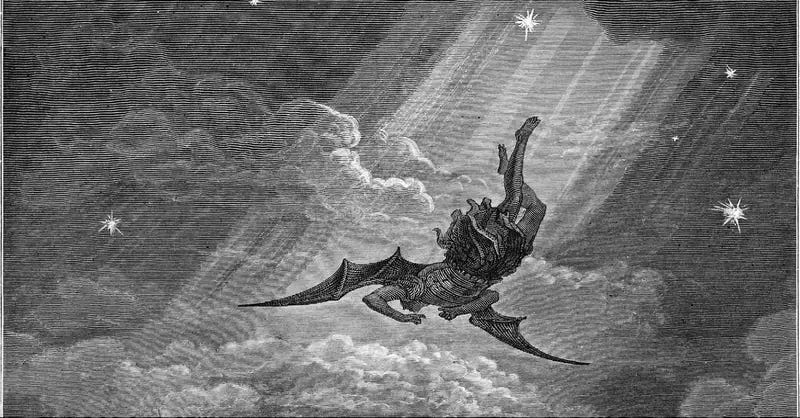

This process results in what Girard terms mimetic contagion. Interestingly Girard views this dynamic as the work of the Devil, who we’ll call by his other name, the Adversary. Working within, his influence exploits our frustrated desire by projecting our anger onto others. He engenders rivalry, allowing envy and jealousy to fester. This negative feeling multiples and becomes contagious, and electrifies crowds into frenzied violence and mob rule.

This dynamic would normally threaten to devolve into war and bloodshed. Girard writes the ancients found means to manage such drama through the use of the scapegoat mechanism. He theorizes this dynamic originates through the Adversary, who projects the sins of the crowd onto an innocent victim. Catharsis is thereby delivered under a false pretense through a lynching. The appearance of justice is delivered at the expense of reflection and compassion. The victim is deemed the necessary sacrifice to keep society going, and it is through this pattern, always hidden, that the Adversary held ancient society under his thrall.

The ancients so revered this mechanism for its ability to manage violence that it is embedded in the founding myths across ancient cultures. It is the honoring of this mechanism that took place whenever ritualized sacrifice was performed in ancient cultures. As we’ll illustrate shortly, Christianity exposed the scapegoat mechanism as the work of the Adversary, and this is the key reason they banned the practice of animal sacrifice.

MYTH

You belong to your father, the devil, and you want to carry out your father’s desires. He was a murderer from the beginning, not holding to the truth, for there is no truth in him. When he lies, he speaks his native language, for he is a liar and the father of lies. (John 8:44)

In the view of the ancients, violence was inevitable. They lived in a fatalistic world where conflict and disaster always lurked nearby, and diplomacy would not often win out. This could be viewed then as a ‘mistaken identity’ of our place in the world, which Girard indicates is the work of the Adversary. He convinces the ancients that they are less than they are, that they are in thrall to Nature and the gods. This belief indicates that Nature destroys its own in order to create anew, and therefore sacrifice is necessary to appease it. Being shown such a lack of compassion, its reasonable then to show a similar lack of compassion to sacrificial victims in order to survive.

For evidence of violence, the list of victims that suffer abuse in ancient myth are too numerous to mention. However particularly worth mentioning are the tragic heroes from Greek myth - eg. Oedipus, Hippolytus, Pentheus and Narcissus.

The tragic heroes all follow a similar arc, being brutally murdered by the forces of Nature for showing insufficient deference to the gods. Inherent in this idea is the victim is always condemned as the source of trouble, and the oppressor seen as a vehicle of righteous justice.

The guilt of the victim is in fact never questioned. To maintain this state of affairs, it is essential the Adversary operate in darkness in order to obtain unanimous acceptance of his action in the world, and thereby control the destiny of human culture.

CHRISTIANITY

But we speak the wisdom of God in a mystery, the hidden wisdom which God ordained before the ages for our glory, which none of the rulers of this age knew; for had they known, they would not have crucified the Lord of glory. (1 Corinthians 2:7-8)

It is the Bible that documents the undoing of the Adversary. For while myth always condemns, the Bible refuses to demonize victims of violent crowds. The Psalms are among the first texts in history that documents the perspective of the victim. And in the Book of Job, we see Job call Yahweh to account for his violent, thoughtless nature while denouncing mimetic contagion.

But it is in the Gospels that the Adversary is most clearly revealed for who he truly is. This is detailed in the Passion narrative, which presents a clear picture of the scapegoat mechanism. A story of an outsider who develops a following and challenges the establishment, who becomes a focal point for frustrated desire and mimetic contagion. A violent rage ensues, with even the disciples cowed into silence as the mob cries out for crucifixion, and Jesus dies on the cross.

However what happens next is remarkable in that it extends on the usual course of events. Christ accepts the violence done to him, and the disciples encounter him rising from his grave, in such a way that subverts the role of the victim. The disciples experience revelation, bearing witness to how Christ has duped the Adversary. For by drawing out his violence and remaining unharmed, he has revealed what must remain concealed. He who only knows might has been undone by a radical weakness, a willing renunciation of violence.

The disciples at the behest of Christ thereafter broadcast what they have witnessed to the world. In doing so, they expose the illusion that had held ancient societies in thrall for millennia. By drawing out the action of the Adversary with such clarity in the Passion narrative, shedding light on what had always been hidden, they triumph by drawing light to that which cannot be taken seriously anymore. The common understanding is reversed, as the victim is declared innocent, and the perpetrator is judged to be guilty.

CONCLUSION

Then the righteous will answer him, ‘Lord when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you drink? When did we see you a stranger and take you in, or naked and clothe you? Or when did we see you sick, or in prison and come to you?’ And the King will answer and say to them, ‘Truly, I say to you, inasmuch as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to Me’ (Matthew 25:34-40)

I’d like to offer a psychological take on the Passion narrative, in order to illustrate how it is relevant to us individually. The mob violence is the projection of our dark side onto others, blaming the other for what one finds unacceptable inside. The projection is a refusal to take responsibility for our desire. The Adversary relies on a lack of self- reflection, where the mob struggle and rage against injustice and thereby become more enmeshed in their projections.

By choosing to instead examine the consequence of our actions, we start to ‘carry the cross’ that only we are meant to bear. This signifies the withdrawal of our projection onto others, and getting in touch with ‘the other’ that lies within our heart. Rather than prolong the drama, we allow ourselves to become the scapegoat, offering ‘no resistance to one who is evil’ (Matthew 5:39).

The recognition of our shadow is a ‘passion’ that involves our whole being. It involves integrating our opposite, thereby making us whole, which is a process signified by the cross. Indeed to hold this tension is to crucify the ego, a ‘passion play’ that activates a deeper process within, bringing forth its and latent powers. In summary, the complete embrace of death through becoming the scapegoat is to discard the hold the Adversary has upon us. This experience destroys our old self, propelling us beyond death into an experience of revelation and grace where we are born anew.

I hope this take has sufficed to illustrate how the Christ narrative has been relevant to so many people for so long. What I’ve drawn out here intellectually is illustrated more effectively in the text itself, for it speaks to the heart. The process I’ve outlined requires one to step outside one’s self and see from the other’s perspective. This is the start of compassion, which is the heart and soul of Christian belief, the ‘love [of one’s] neighbor as thyself’ (Mark 12:31). It is from the story of Christ that our natural disgust for scapegoating today originates, where we now place the individual at the center of society, presuming innocence on the part of the victim. Indeed one does not need to look far to see this ‘concern for the victim’, for greater or worse, still continues to have an iron grip on Western thought today.

Where'd you go man? You had a cool thing going here.